The classic Lake District sub-24-hour fell challenge

The Bob Graham Round is an iconic sub-24-hour fell challenge which traverses much of the Lake District National Park. OS Champion Alex Staniforth shares his experience of the Round and why this epic Lakeland route makes such a memorable run or walk.

What is the Bob Graham Round?

The Bob Graham Round is one of three sub-24 hour mountain challenges in the UK, the other two being the Ramsay Round and the Paddy Buckley Round. It was first conceived in June 1932, when Keswick hotelier Bob Graham broke the 24-hour Lakeland Fell record by crossing 42 fells in the Lake District, over 66 miles with a whopping 27,000ft of ascent. (Everest is 29,035ft, just for scale). The route can be walked, split into multiple day sections, but to be officially ratified in the ‘Bob Graham 24-hour Club’, you must run the challenge under 24-hours. Each runner must be accompanied by a witness on each summit with a team of support runners usually taking turns on each leg.

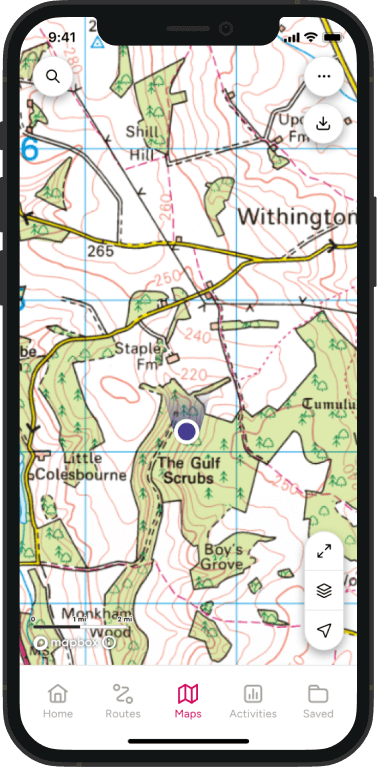

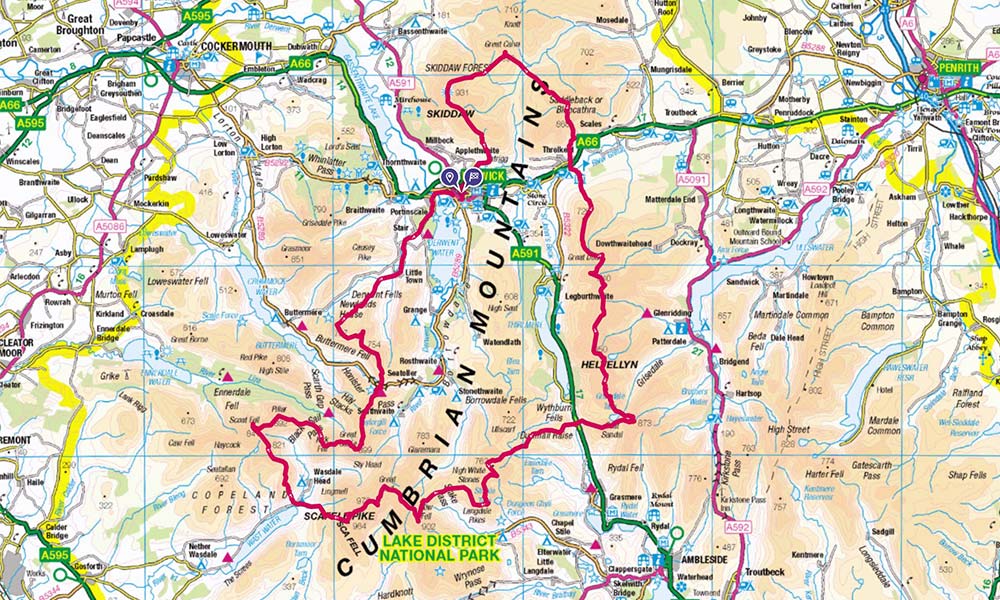

Bob Graham Round Route Map

The 24-hour challenge

Over 200 people attempt the challenge each year, with less than half being successful. As of 2022, the Bob Graham 24-hour Club has 2,712 members. In 2020, Beth Pascall bettered the women’s record (also known as a Fastest Known Time) in a whopping 14 hours 34 minutes. The men’s record was knocked even further in 2022 by Jack Kuenzle in a time of 12 hours and 23 minutes, which even the strongest local support runners struggled to keep up with!

What is the best Bob Graham Round route?

The route starts and finishes at the Moot Hall, Keswick, and can be taken on either clockwise or anti-clockwise, traditionally in five stages or legs. You choose your own lines and routes between the 42 named fells, but good local knowledge gets passed around. More confident and experienced runners might take the scramble up Broad Stand onto Scafell instead of Foxes Tarn and go off-piste on more technical descents to save time. There’s a mix of everything – from rocky mountain paths, the summit of Scafell Pike, grassy fell sides, muddy single track, fire roads, boulders, scree and a few miles of tarmac at the start and finish back to Keswick. It’s as much a navigational challenge as a huge feat of physical endurance, and most successful members will spend considerable time ‘recceing’ and obsessively studying the route to avoid these mishaps – this build up is often the most rewarding part of the journey.

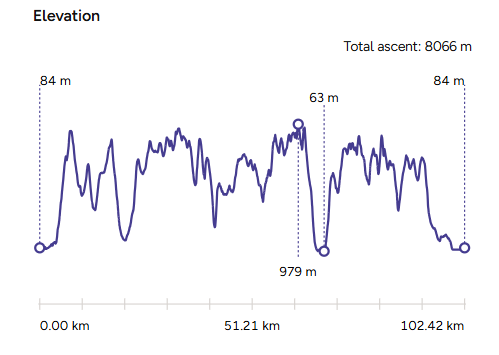

What’s the total distance on the Bob Graham Round

As described above the distance will depend on the exact route you take but in this route on OS Maps it’s 102km

What’s the total ascent on the Bob Graham Round?

In total you will climb 8066m (depending on your chosen route) – but as it’s not all in one go you wont need to worry about oxygen!

Paper maps for the entire route

EXPLORE THE

OS Shop

We are with you every step of the way. Shop our trusted walking and hiking maps and guidebooks so you can explore the outdoors with confidence.

Go to the shop

Walk or run

Local legend Billy Bland famously ‘walked’ the route in one go to prove this was possible, albeit Billy Bland hardly represents the average person. Still, unless you’re chasing record times, ultra and fell-running involves a lot of walking on steeper sections. I’m yet to see anyone run up Steel Fell from Dunmail Raise! But if you don’t fancy the 24-hour pressure, many people enjoy walking the round over a few days, and wild-camping along the way. There are good bus links between Keswick and the end of leg two and leg four if you want a longer day out experiencing some of the route.

Seduced by the Bob Graham Round

Regrettably, I was also seduced by the mystery of this legendary feat. A local initiation, of sorts. The Bob Graham Round has become the equivalent of a marathon in road running, and I wanted to earn the stripes. Personally, I had always been interested in the idea of going solo and unsupported, in a similar guise to many of my previous challenges. I wasn’t too bothered about being officially ratified and thought the sense of achievement would be greater for a solo round and afford me more flexibility around logistics. Being based on the edge of the Lake District gave me the perfect opportunity.

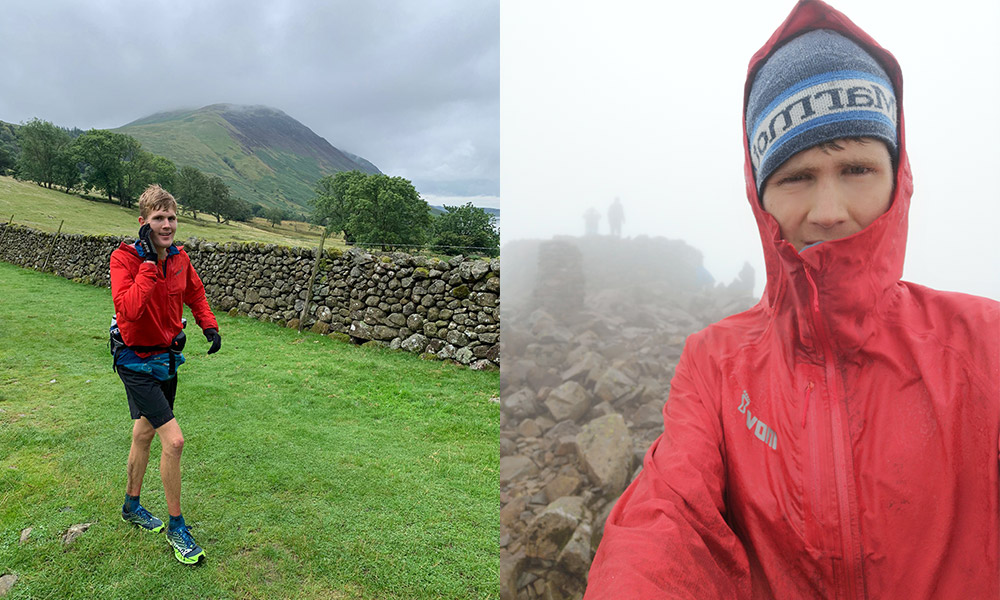

My experience of the Bob Graham Round 24hr challenge

Over the last five years I’d ran the separate legs of the route several times, sometimes combining one or two. The thought of doing the whole thing often felt insurmountable until I had completed my 3 Peaks Run in 2020. I finally attempted the full round in August 2021 after six months of dedicated planning. I had postponed my first attempt due to a possible cracked rib on a training run up Dale Head. With the summer window passing and days growing noticeably shorter, the worry of missed opportunity got the better of me, and I went out in sub-par conditions. It didn’t go too well.

Heavy rain and poor visibility brought slippery conditions underfoot and led to some navigational errors, both of which lost considerable time, particularly on the rockier sections around Scafell Pike and Great Gable. A brief break in the weather brought an amazing sunrise across the Langdales. The weather improved slightly on the final two legs, and a friend Peter surprised me at Wasdale with some hot food and drink when I would otherwise have likely quit. I pressed on to finish what I had started, albeit knowing the sub-24 hour train was long departed and was no longer self-supported. After this hot brew revival, I even managed leg five in the scheduled time, legging it down the final summit, Robinson, with the end firmly in sight. I finished in 27 hours 35 minutes. Not long after celebrating and taking in the moment, I had collapsed and ended up in hospital with hypothermia.

Lessons learnt on the Bob Graham Round first attempt

I was naïve to underestimate the Bob Graham Round and the difference that a support team can make. Having a support team is far more than a friendly face and a cup of tea with two sugars. I never intended to undermine this but sometimes we must learn the hard way. The fell-running community is a selfless thing: a collective effort to achieve common goals, and sharing that experience is what makes the Bob Graham Round so special.

There’s also a fine balance when it comes to being ready. Waiting for perfection can be the devil in the detail. Changing the date due to weather can bring logistical headaches for you and the support team, and this often pushes us out when we’re not physically ready or conditions are against us. For a challenge of this scale, you need as many factors working in your favour as possible. This seems obvious, yet so many people still get it wrong. Myself included.

Most importantly I learnt that hypothermia doesn’t just happen in winter. Putting myself in hospital is certainly not something I’m proud of, but all I can do is educate others. If it caught me off guard, then it will catch others off guard too. As a non-drinker many of my friends still joke it was the obligatory pint of beer at the finish that floored me! Hot food and drink at checkpoints and getting spare warm layers on (like a down jacket) as soon as you stop moving is key, and again your support team will often be on this when you’re too tired to remember.

Failure often teaches us more than achieving our goals. Sometimes this is due to factors beyond our control: but either way, the most important thing is to own it, learn from it and get back up again.

Future plans

The elusive sub 24-hours feels like unfinished business. With the new experience, appreciation and respect gained, I’m keen to complete the round in the traditional supported style, and I’ve dreamed of making a winter attempt if the rare stars of superb conditions and the opportunity align one day. Last April I completed the 105-mile Lakes, Meres and Waters route which should hopefully make the 66-miles feel slightly less overwhelming.

However, there’s more elusive and less-trodden rounds and challenges in the Lake District still to be discovered though, and it’s nice to give these some attention instead. If we don’t give it a go, then we fail by default.

Bob Graham Round Summit List and Heights

| Summit Sequence | Location | Summit Height (m) |

|---|---|---|

| Start and Finish Line | Moot Hall, Keswick | |

| 1 | Skiddaw | 931 |

| 2 | Great Calva | 690 |

| 3 | Blencathra | 868 |

| Road Crossing | Threlkeld | |

| 4 | Clough Head | 726 |

| 5 | Great Dodd | 857 |

| 6 | Watson’s Dodd | 789 |

| 7 | Stybarrow Dodd | 843 |

| 8 | Raise | 883 |

| 9 | White Side | 863 |

| 10 | Lowerman | 925 |

| 11 | Helvellyn | 950 |

| 12 | Nethermost Pike | 891 |

| 13 | Dollywaggon Pike | 858 |

| 14 | Fairfield | 873 |

| 15 | Seat Sandal | 736 |

| Road Crossing | Dunmail Raise | |

| 16 | Steel Fell | 553 |

| 17 | Calf Crag | 537 |

| 18 | High Raise | 762 |

| 19 | Sergeant Man | 736 |

| 20 | Thunacar Knott | 723 |

| 21 | Harrison Stickle | 736 |

| 22 | Pike O’ Stickle | 709 |

| 23 | Rossett Pike | 651 |

| 24 | Bowfell | 902 |

| 25 | Esk Pike | 885 |

| 26 | Great End | 910 |

| 27 | Ill Crag | 935 |

| 28 | Broad Crag | 934 |

| 29 | Scafell Pike | 978 |

| 30 | Scafell | 964 |

| Road Crossing | Wasdale Campsite | |

| 31 | Yewbarrow | 627 |

| 32 | Red Pike | 826 |

| 33 | Steeple | 819 |

| 34 | Pillar | 892 |

| 35 | Kirk Fell | 802 |

| 36 | Great Gable | 899 |

| 37 | Green Gable | 801 |

| 38 | Brandreth | 715 |

| 39 | Grey Knotts | 697 |

| Road Crossing | Honister Pass | |

| 40 | Dale Head | 753 |

| 41 | Hindscarth | 727 |

| 42 | Robinson | 737 |

| Start and Finish Line | Moot Hall, Keswick |

This guide has been updated, it was first Published on March 13, 2023