History-lover and GetOutside Champion Mary-Ann Ochota explores some of the history behind Britain’s much loved pub names – and ways that you can tell what’s occurred in the years before.

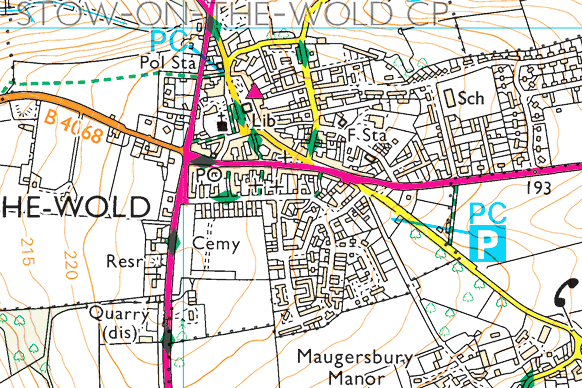

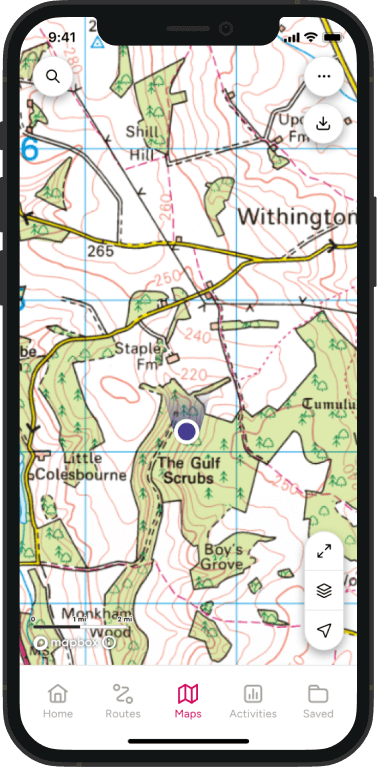

Britain was built on pubs. And even though many ‘locals’ have closed in recent decades, there are still more than 55,000 public houses in Britain. You’ll be pleased to know that they are often marked on OS 1:25,000 scale (Explorer) maps. Look out for that blue pint tankard symbol – standing proud at the centre of a village, or as little beacons of blue on lonely roads. They’re some of the most enjoyable features to navigate by!

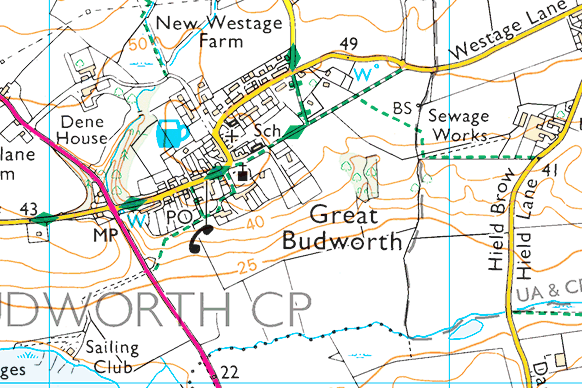

The George & Dragon sits in the heart of the village, opposite the church. Image: The George and the Dragon

Great Budworth, Cheshire. OS Grid Reference: SJ 66 77

Some pubs are Free Houses, meaning they can sell any beer the landlord wishes, others are ‘tied’, where a brewery or pub company dictates what beers can be sold.

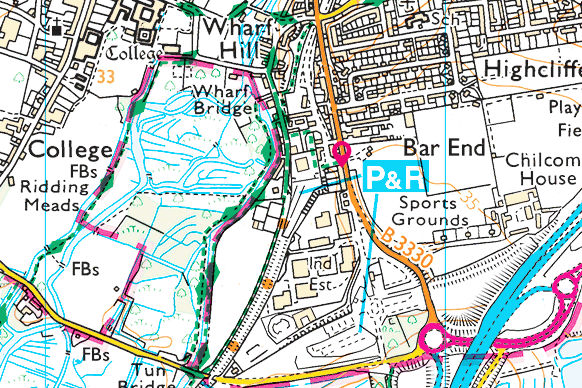

An Inn traditionally provided accommodation and stabling as well as food and drink, and coaching inns were regular stops for stagecoaches carrying passengers and mail between major towns and cities. You’ll notice many have courtyards of stable buildings (now often converted) through a gateway high enough to give a horse-drawn coach clearance.

Look for: Cobbles

Before you head in for a pint, have a look around the yard. Look for traces of original cobbled surfaces, designed to provide a low-cost, very durable surface that was smooth enough for wheeled carriages, but provided enough grip to prevent horses from slipping.

You may see fancy cobble designs, where the stones have been bedded into the ground end-on. These patterns use more stone and require more labour to construct – rich landlords showing off!

Also look out for stone steps used as mounting blocks to help people get on to their horses, metal rings in walls used to tether horses securely, and drinking troughs. Stable doors may still be in position, or blocked up, and look up for pitching eyes, the first floor circular windows that enabled groomsmen to drop hay and straw from haylofts into the yard below.

Swinging Signs: Open for business

In Roman times wooden poles hung with vine or ivy leaves were placed outside drinking houses to show they were open and serving. The tradition continued after the Romans left, and in medieval times a horizontal ale-stake would be hung with an ivy garland or bush at the end to indicate fresh beer was ready for sale.

Painted board signs were used from medieval times, and a law was passed in 1393 stating that if a sign wasn’t hung, the tavern owner would forfeit his or her beer.

Picture signs were important when many people were illiterate – a crown, bull’s head or star were easy symbols to paint and recognise.

Look for: Ivy

Most pubs no longer hang vines or ivy outside, but look at the brackets that hold the sign – some of them incorporate vine, grape or ivy shapes.

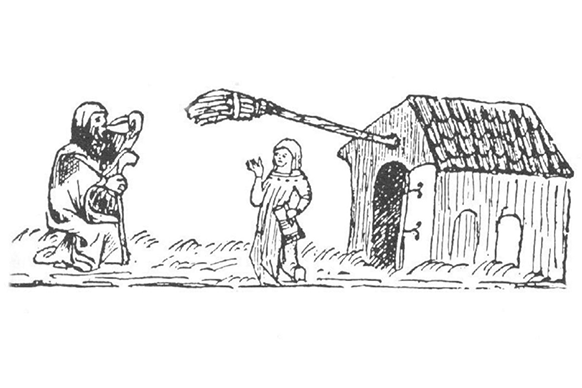

Medieval ale stake

Cast iron vine leaves on the sign outside Ye Olde George Inn, East Meon, Hampshire SU 680 221

What’s in a name?

Many pubs have changed their names multiple times, reflecting changes in politics, patronage or ownership. The Rising Sun, for example, was the badge of King Edward III (who reigned from 1327–77). Although records are sketchy, you can be sure there were more Rising Suns in 1366 than there are in 2016! You may still sometimes spot a little sliver of a rising sun at the top of a pub sign.

Other pubs retain historical links – ‘Fox and Hounds’ and ‘Horse & Hounds’ were often meeting points for the local hunt. Inns on routes traditionally used to drive animals to market may be called ‘The Drovers’ or commemorate the origins of customers, like ‘The Highland Laddie’ (which can be found in Darlington, Glasson in Cumbria, Stockton-on-Tees and Hull).

Ewan Munro/Flickr The Crown | Ewan Munro/Flickr The Crown (2) Michael Button/Flickr The Swan | Ian S/Geograph Highland Laddie | Peter O’Connor/Flickr The Sun Inn

Quirky modern pub names have a longer history than you might think: an editorial in the Spectator magazine in 1710 bemoaned the fashion for foolish pub names, like ‘Blue Boar’ and ‘Flying Pig’. Campaigners are currently attempting to protect pub names under planning permission law.

Red Lion

Black, white, red, golden…many lions crop up on pub signs, reflecting the heraldry of local or national patrons. Red Lions are the most common (there are more than 500), and are often attributed to 14th Century noble John of Gaunt or to King James I of England (who reigned 1603-25). James allegedly demanded that all public buildings display the Red Lion to show allegiance to him. In fact, there’s no evidence that James made such a demand, and as the Red Lion features in the heraldic badge of more than 150 English families, it’s just as likely to have links to a local patron as to the king.

White Hart

Deer, swans, dogs, ducks, bulls, foxes and horses all feature in pub names. The white hart, a rare pale male red deer, was the heraldic badge of King Richard II (reigned 1377-1399) and is usually depicted with a chain and golden collar or crown round its neck.

King’s Head

Many pubs have changed names in their history. In the 16th Century, following King Henry VIII’s split with the Catholic Church and the decades of anti-Catholic sentiment that followed, ‘Pope’s Head’ pubs were frequently renamed ‘King’s Head’, a safer declaration of allegiance. The Lamb and The Mitre, both suggesting Catholic connections, have survived rather better.

The Crown

The second-most popular pub name in the country, and an easy statement of allegiance to the monarch. Also a very simple symbol to remember, even in a time when most people couldn’t read or write.

Black Boy

Now a rather controversial pub name, records of ‘Black Boy’ inns go back at least 250 years. There are four potential origins of the name – and no-one’s really sure which is the real explanation! The pub could be named after:

- a character with skin darkened by their work, like chimney sweeps or miners covered in soot or coal-dust.

- King Charles II, who was nicknamed ‘Black Boy’ by his mother, Henrietta Maria of France because of his dark hair and complexion. The name was adopted by Charles’ supporters fighting for the restoration of the Monarchy in the 1650s. Inns using the Black Boy name were possibly declaring their royalist allegiance against Oliver Cromwell’s parliamentarians.

- The least watertight etymology is that they’re named after local dark-coloured shipping signals, the name being a misspelling of Black Buoy.

Hidden Histories: A Spotter’s Guide to The British Landscape

Entertaining and factually rigorous, Hidden Histories: A Spotter’s Guide to the British Landscape by British broadcaster and anthropologist, Mary-Ann Ochota, will help you decipher the story of our landscape through the features you can see around you.