Why did Ordnance Survey have a box of spiders?

When we think of map-making, we often imagine satellites, GPS, and digital precision. But the origins of Britain’s national mapping authority, Ordnance Survey, are rooted in something far more unexpected: spiders.

In a recent video by Chris Spargo featuring Simon Navin, Head of Geospatial Services at Ordnance Survey, we’re taken on a fascinating journey through the history of mapping in Great Britain. While the story begins with military strategy and mathematical precision, it’s the spiders that steal the show.

Mapping Begins: A Baseline of Precision

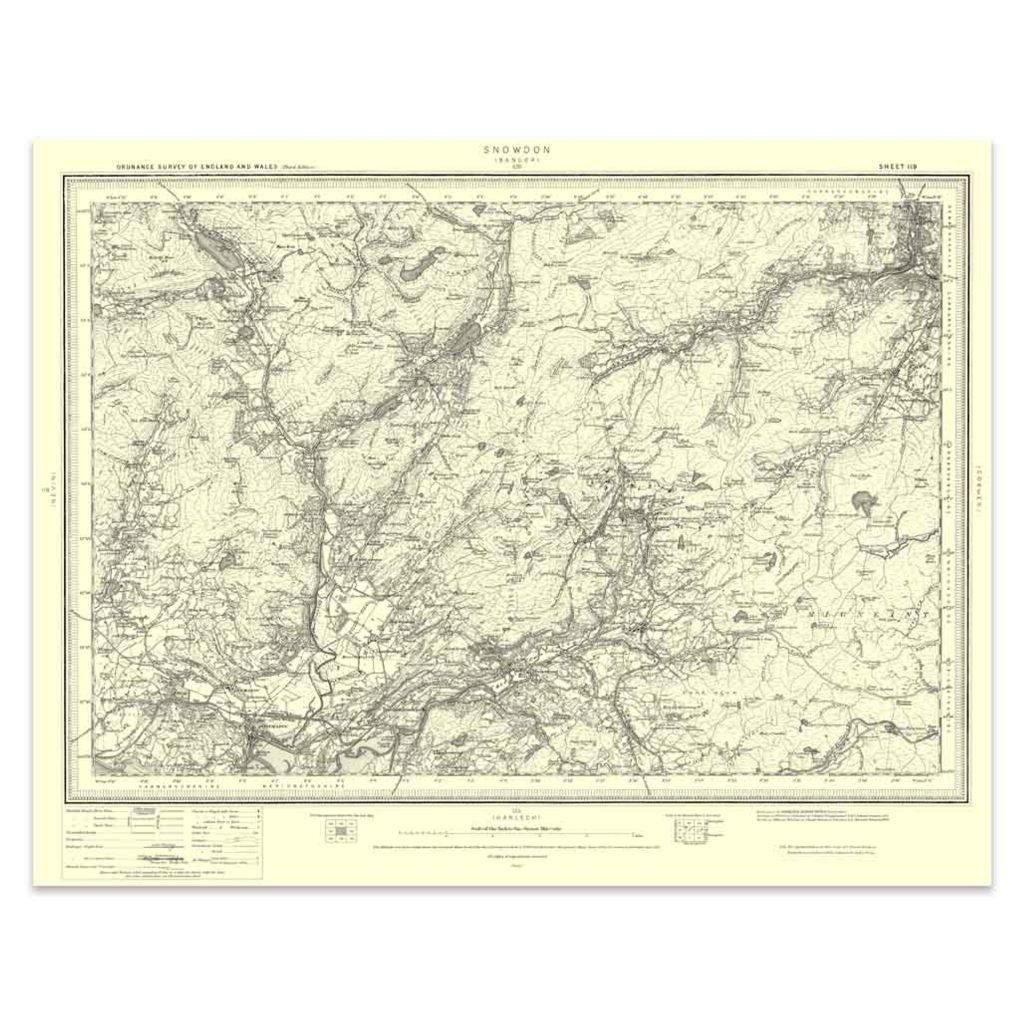

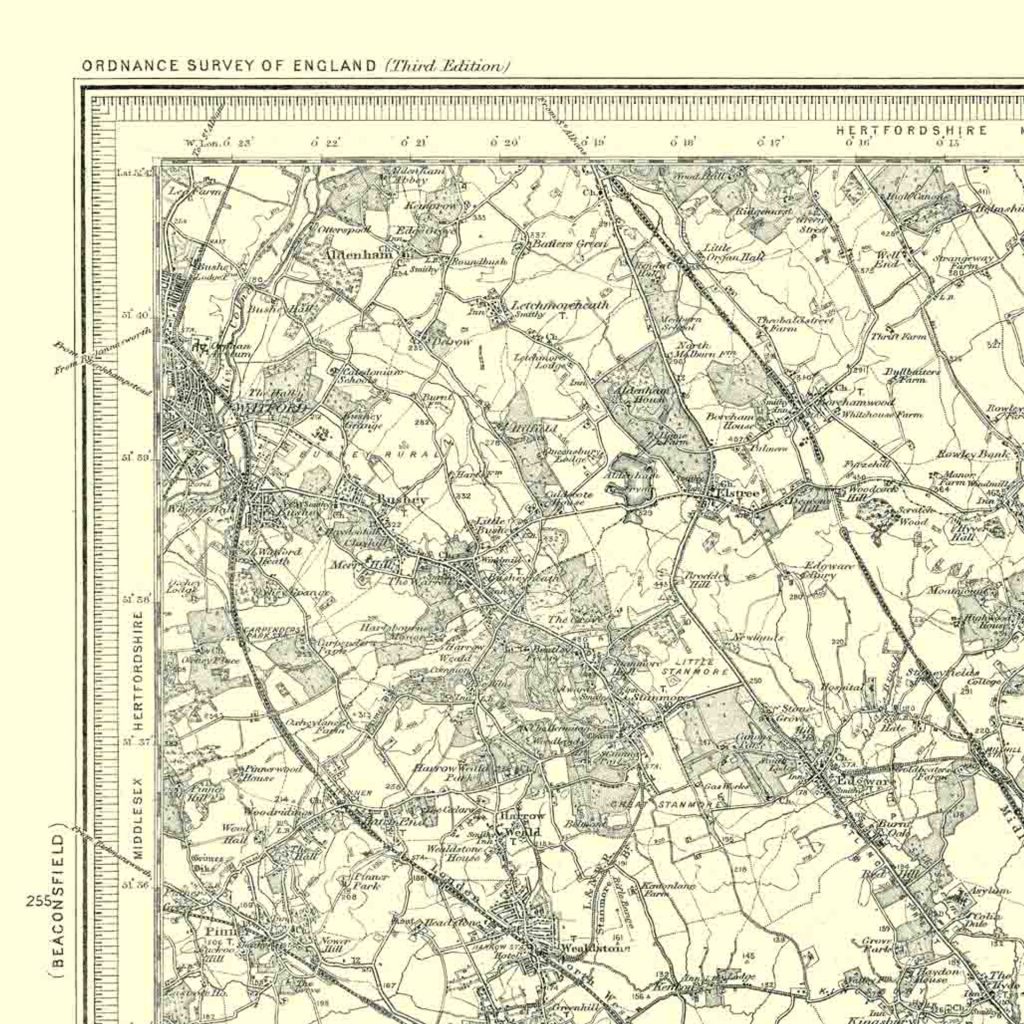

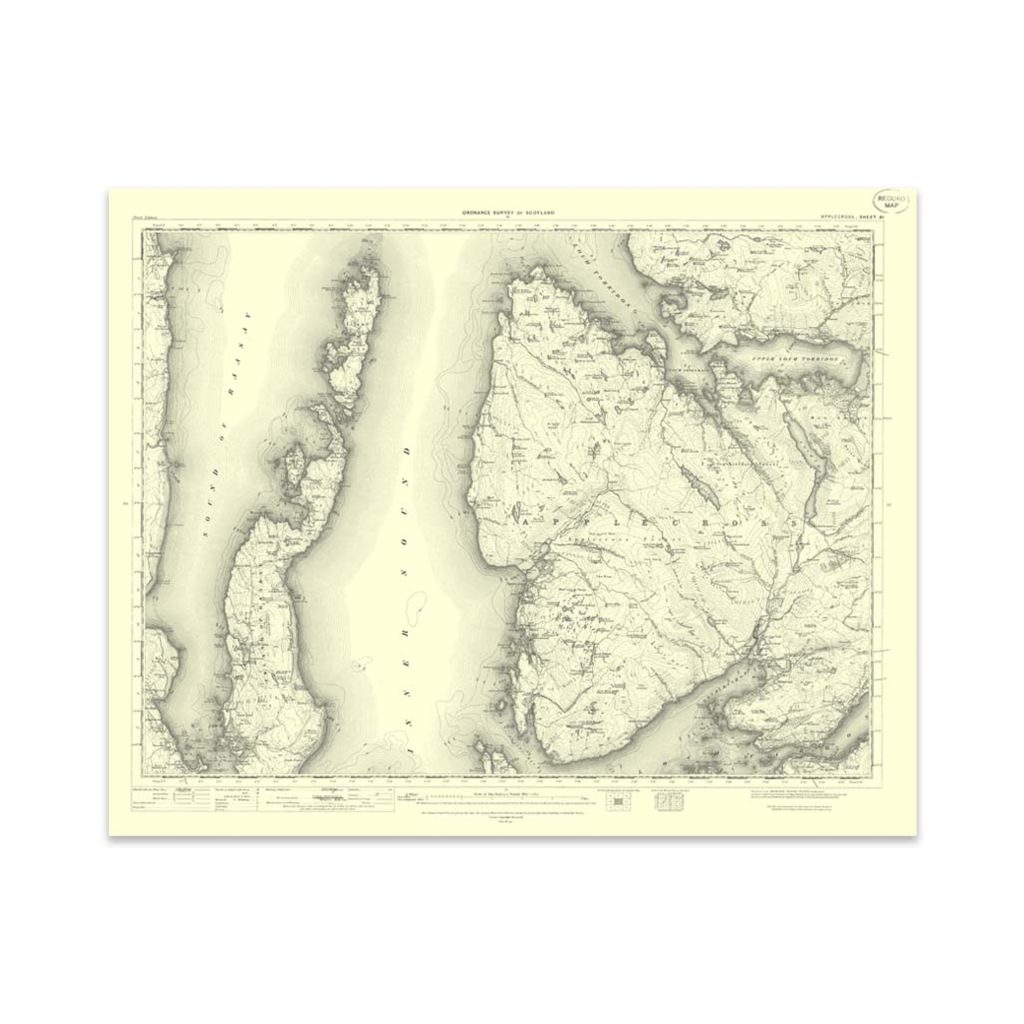

The first Ordnance Survey map, created in 1801, depicted the county of Kent. Before this, maps were largely artistic interpretations. They were visual guesses rather than measured realities. That changed with Major-General William Roy, who laid the groundwork for modern mapping by establishing a baseline west of London, stretching to what is now Heathrow Airport.

Using a 100-link surveying chain, Roy and his team meticulously measured 27,404.01 feet of flat terrain. This baseline was critical. Every subsequent calculation depended on its accuracy. Even a tiny error could ripple through the entire mapping process.

Measuring Angles: The Theodolite

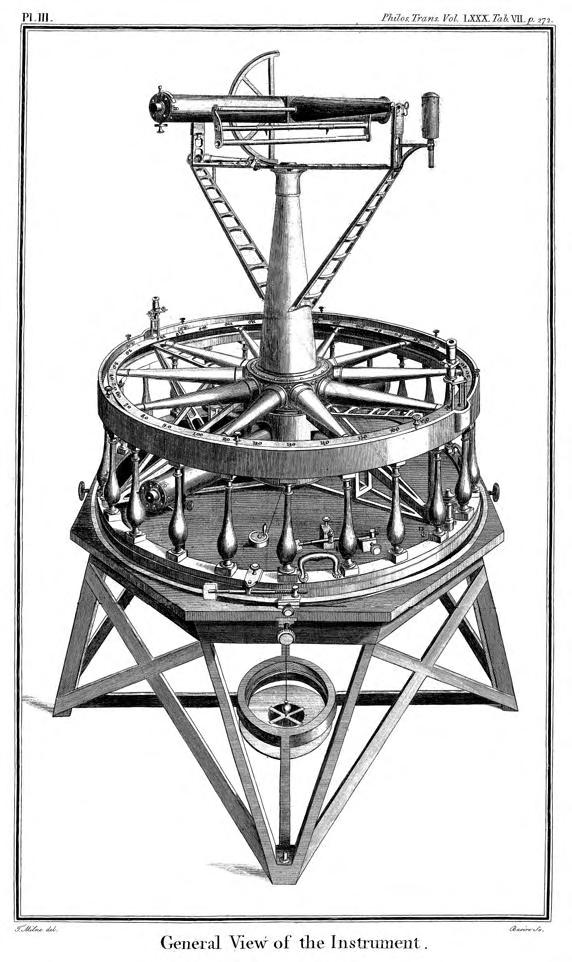

Once the baseline was set, the next step was measuring angles using a device called a theodolite. The first one, commissioned from master instrument maker Jesse Ramsden, took three years to build. It was so precise and valuable that its purchase date is now considered the founding moment of Ordnance Survey.

But even the most sophisticated instruments needed one final touch to achieve true precision: crosshairs.

Enter the Spiders

Here’s where things get wonderfully weird.

To create the finest possible crosshairs for their telescopic instruments, Ordnance Survey turned to nature. Traditional materials like wire or human hair were too thick and prone to sagging. But spider silk, specifically from the European garden spider (Araneus diadematus), was strong, thin, and stable.

So Ordnance Survey began farming spiders.

Surveyors would collect spiders from the gardens around their buildings, place them in special boxes, and harvest their webs. These webs were then carefully stretched across lenses using delicate tools such as forks, tongs, and prongs. This formed ultra-fine crosshairs. Once the webs were in place, the spiders were released back into the wild, ready to be called upon again.

Some of these spider webs are still preserved today. Remarkably, this technique was used until as recently as the 1980s. Only with the advent of laser-etched glass did spider silk finally retire from its role in national cartography.

Why Accuracy Mattered

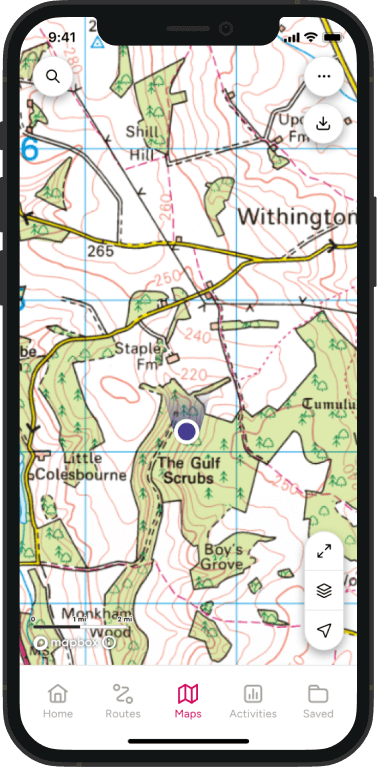

The use of spider silk wasn’t just a quirky footnote. It was essential. Every measurement, every angle, every map depended on pinpoint precision. The accuracy of those early instruments laid the foundation for the maps we rely on today, whether we’re hiking a trail or navigating a city.

So next time you open OS Maps or admire a beautifully detailed route, spare a thought for the humble spider. Without its silk, Britain’s mapping history might have looked very different.

For more fascinating videos be sure to subscribe to Chris Spargo’s Youtube Channel