Adventures Around the Standing Stones of Ancient Britain

There are drawers full of maps in our home, charting the trips we have made all over the country, from the Land’s End peninsula (OL102) and North Pembrokeshire (OL35) to the Dark Peaks (OL1) and Orkney West Mainland (OL463). Some of these maps are especially well used, with fraying creases and mud stains that signify multiple return visits. Marlborough & Savernake Forest (OL157) is one such – this is the map that shows Avebury, the megalithic landscape where I first fell in love with standing stones.

Other maps are looking quite old now: Landrangers with purple covers, priced at £1.40. These belonged to my husband Stephen and he acquired them long before I met him, when he was a teenager in South Wales, plotting hikes with his friends in the Black Mountains and the Brecon Beacons.

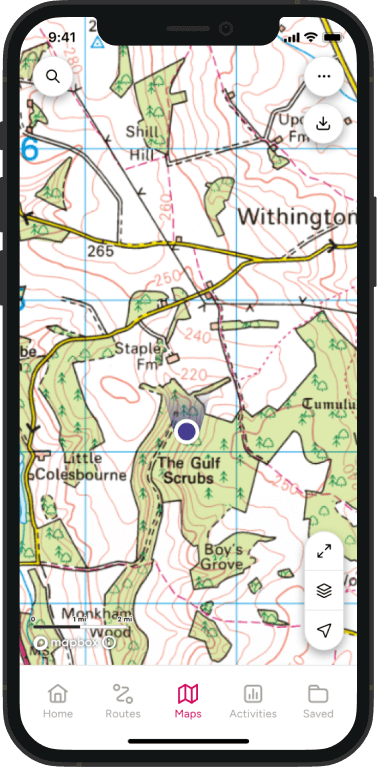

Whenever I travel anywhere new, I get a map. Although these days I always download the digital version too, nothing beats the exhilaration of unfolding the crisp sheets and reading for the first time the names of villages and farms, woods and hills; of scanning for nearby prehistoric sites and spotting the Gothic script of a Cairn, Fort, Settlement, Hut Circle, Tumulus or – even better – Standing Stone or (best of all!) Stone Circle. And then tracing with my finger the dotted lines of the footpaths that will get me there.

An OS map functions in multiple dimensions: it captures the landscape through its contour lines and field boundaries and the variable shading that indicates water or wood, bog or scree; and it also preserves the history of a place through the old names, the rights-of-way and of course the markers of ancient sites, some of which (I discover when I get there) are barely or not at all visible on the ground, so the barrow or cairn or settlement lives on only through the map and the imagination of the map user.

On Fyfield Down above Avebury there’s a wondrous thing: a sarsen stone named the Polisher for the parallel grooves and dish-shaped indentation ground into it by people shaping and polishing axe-heads 5,000 years ago. If you search up this site online, you’ll find all sorts of directions that are either too vague or too complicated (involving compass bearings which I’m sorry to admit I still don’t know how to do). On our first attempt, we wandered fruitlessly among hundreds of identical-looking prone sarsens until my kids’ patience ran out.

A few months later I was back, this time armed with better instructions, and it turns out that locating the Polisher is not that hard. All you need to do is walk along the Ridgeway to point 257 on the map (OL157), go eastwards through a gate and then weave through the sarsens towards a prominent pyramid-shaped stone to find the Polisher lying very close by.

It’s a marvellous ancient site on the sarsen-littered downland and you are unlikely to encounter anyone else there, so if (like me) you are that way inclined, you are free to run your fingers down the deep, marbled grooves and try to imagine the people who made them all those thousands of years ago.

My children Alex and Ava have grown up playing hide-and-seek among the stones, at circles from Boscawen-ûn on the Land’s End peninsula to Calanais in Lewis in the Outer Hebrides (OS459).

I have a very funny video of Stephen hiding from Ava behind one of the southern entrance stones at Avebury; every time she rounded the corner of this huge megalith he would slip round the other side (as the stone is really massive, he kept this going for some time). If you were to ask Alex and Ava what they think about standing stones, they would not answer with unalloyed joy and enthusiasm, but what they have always loved is the adventure of tracking them down.

In Scilly, which in addition to being breathtakingly beautiful also enjoys one of the densest concentrations of prehistoric sites in Britain, I got hold of a list of all the Bronze Age chambered cairns in the islands complete with grid references that can very handily be plugged into the digital app (OL101).

Many happy hours were spent wandering phone-in-hand over Scilly’s downlands in search of megaliths, and though a lot of these sites turned out to be highly ruinous – for the committed stones geek only – others were unmistakably ancient chambers and a joy to discover among the heather and gorse and natural boulders.

Most fun of all was kayaking across from Green Bay on Bryher (where, incidentally, a prehistoric stone wall is visible at low tide) to the dazzling white shell-sands of Samson and climbing up to the ancient burial grounds on top of the island’s two hills. We explored the ruins of cottages abandoned when Samson’s last inhabitants left in 1855 and crawled into the prehistoric entrance graves which are still, after several thousand years, roofed with their capstones. From up here you can see over all Scilly – it felt like we were flying.

OS Maps Capture the Past and Present…

I mentioned above that an OS map captures the past and present of a place and I would add a further dimension: it also preserves the memories of the people who use it. Each of those maps in the drawers in my house transports me back to adventures shared with people I love.

I mentioned above that an OS map captures the past and present of a place and I would add a further dimension: it also preserves the memories of the people who use it. Each of those maps in the drawers in my house transports me back to adventures shared with people I love.

From the map of the north-western English Lakes (OL4), where Stephen and I climbed together pre-kids and saw Castlerigg stone circle for the first time, to Maidstone & The Medway Towns (OL148), where the four of us spent many a Sunday exploring the very ancient sites that (amazingly!) survive between the Kentish urban sprawls, to the map of Land’s End, where we returned again and again at October half-term to hunt down the insane bounty of standing stones there, these maps recall the best times of my life.

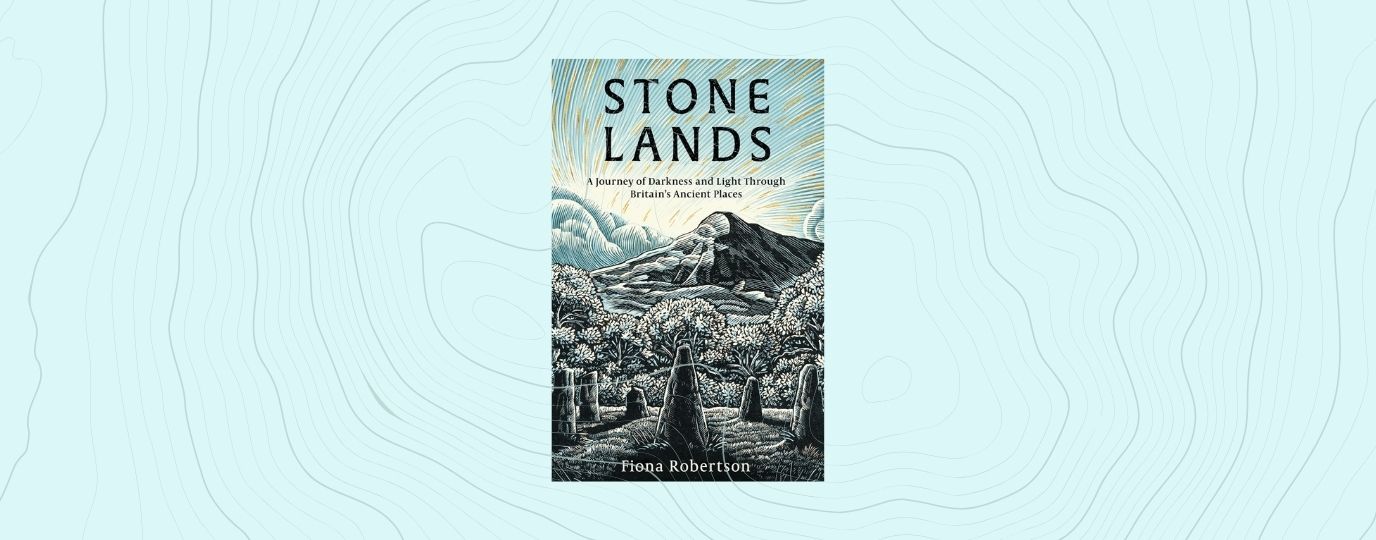

If Fiona’s story has sparked your interest in stone circles and ancient megaliths, you’ll love her new book – Stone Lands. It explores how her journey through Britain’s ancient sites became a powerful way to navigate grief, and why this beautifully written memoir is a must-read for anyone drawn to landscapes, history, and personal resilience.

By Fiona Robertson

Fiona Robertson is a writer, editor and the author of Stone Lands (Robinson, 2025). A committed megalith enthusiast, she has dragged her family over many a boggy moor (OS map in hand) in search of standing stones. She is passionate about archaeology and folklore, and in a former life as a publishing industry professional enjoyed building a list exploring these topics. Follow her stones adventures on Instagram: @stone_lands and read her story of expoloring Britains ancient sites with her family in her post ‘Mapping Memories‘.